I’ll never forget the last time my father helped me. It was a typical situation, repeated dozens if not hundreds of times over the previous three decades: Something would go wrong in the afternoon or evening, and my mornings-only caregiver would be unavailable to return for off-hours assistance. Most of the time, my dad would be available, sometimes reluctantly, but available nonetheless. He was not the kind of guy who could easily say “no” to his children — especially to his youngest son who’d been paralyzed at the age of 17.

That last time was no different, with one major exception: At the time, shortly before Thanksgiving of 2010, neither dad nor anyone else was aware that he was dying. We knew he was ailing, but the extent of his illness was unknown, even by his doctors. Pancreatic cancer was a prime suspect, but a firm diagnosis remained stubbornly elusive. Dad felt tired, and was suffering from mild abdominal pain, but he was the kind of guy who’d remain stoical about how he was feeling. He didn’t want to worry anyone, so there he was, late on a dark, blustery November afternoon, arriving at my house as he had countless times before, responding to my call for help. (More often than not, this involved a quick clean-up and change of pants; you can guess the rest.)

This time something was obviously wrong. Dad was clearly lacking energy, and pain was draining what little vitality remained. As he was getting me dressed and helping me get transferred back into my wheelchair, I watched him struggle and, for the first time in over 30 years, he needed a few breaks to rest.

Was I “Taking Advantage”?

As he rested, I was struck by a tidal wave of guilt and shame. I’d felt that way before, less severely, when I’d relied too heavily on my dad’s good-natured availability. Despite his weakened condition I had placed my needs above his, and as dad sat on my bed, tired and quietly frustrated, all I could think was that I was a lousy and selfish son who had exploited my father’s devotion for decades. I had never taken his kindness for granted, but for a variety of reasons I had allowed myself to expect and depend on it.

Less than two months later, on January 18th, 2011, upper bowel cancer claimed my father at the age of 79. I was with him (and my older brother) when he died, reassuring him that I’d be OK and had made appropriate plans to have my caregiving needs met – plans, I daresay, that I should have made many years earlier, but, well…as the saying goes, it’s complicated.

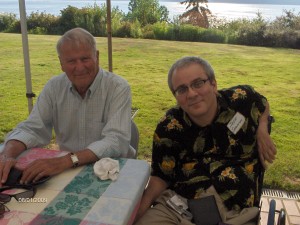

It’s no exaggeration to say that my dad was my most reliable caregiver, not because he worked as many hours as my privately hired caregivers, but because he was almost always available, no questions asked. Even when he wasn’t, he would often leave a social engagement early on my behalf, or would delay plans so he could help me on short notice. For all of this and much, much more, I can unequivocally say that my father, Gerald Arthur Shannon, Jr. (1931-2011), was my hero. He had faults and foibles like anyone else, but it didn’t matter. My dad “Jerry” was my hero.

It’s no exaggeration to say that my dad was my most reliable caregiver, not because he worked as many hours as my privately hired caregivers, but because he was almost always available, no questions asked. Even when he wasn’t, he would often leave a social engagement early on my behalf, or would delay plans so he could help me on short notice. For all of this and much, much more, I can unequivocally say that my father, Gerald Arthur Shannon, Jr. (1931-2011), was my hero. He had faults and foibles like anyone else, but it didn’t matter. My dad “Jerry” was my hero.

Compared to privately-hired caregivers who are not always available, relying on parents for back-up caregiving is an easy, default alternative. My dad may have grumbled a few times when I’d interrupt his day (or even his dinner) to ask for a favor, but for the most part he wanted to be available for me. He volunteered for the job. Likewise, I preferred him because, well, he was my dad and we had a solid, mutually supportive relationship. In return for his reliable backup, I would make myself available whenever I could return the favor. More often than not, this involved helping him with a computer or software problem. I’d had a similar arrangement with my mother before she died in 1988: She’d been a reliable back-up, too. Helping me was something she wanted to do, and I would reciprocate any way that I could.

First, Seek Other Alternatives

It was a workable situation, but the prevailing wisdom (among families and rehab counselors) is that parental or family-member backup should, if possible, be avoided. If your SCI situation allows it, family members should remain just that: parents and siblings who are not your caregivers. For many, however, financial need and family dynamics turn at least one, and sometimes all family members into well-trained caregivers, even if it’s just during travel and special occasions.

There are, of course, other alternatives. Your first step should always be to connect with a DSHS social worker (if you financially qualify for their services) or contact all home-healthcare agencies in your area to see what help they can provide. It’s a lot like job-searching, except you’re the employer, looking for the best hires you can find. If you can take the time to network with home-care referral services, you can build a broad base of caregiver contacts (using want ads, etc.), as a way to avoid family-member back-up.

My current circumstances allow for reliable, agency-provided caregivers, and that’s been a blessing.

Depending on my father drew us closer over the years – closer, I think, than we would’ve been had my injury never occurred. Still, “unburdened” is the keyword here: How much do you want to burden your family, as opposed to freeing them from caregiver obligations? Do you feel like a burden when you depend on them? Do you resent them because you’re dependent on them? Do any of them resent you? What family vs. caregiving conditions are you willing to accept, if any? These are not easy questions, but the earlier they’re answered post-injury, the better.

Got some caregiver experiences of your own to share? Please tell you story below.

Leave a Reply