Disabled People Like Me Have Always Been Vulnerable To disease. Let Us Show You The Ropes.

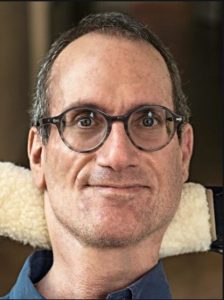

By Ben Mattlin

May 6, 2020

I keep hearing about how disabled people are panicked over COVID-19. As a disabled person, I know this is true. But media reports are missing an important point about us.

The fear and outrage are real. I was born with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a neuromuscular weakness, and have never stood or walked. My respiratory muscles are so weak that the slightest cold could kill me. So my risk from this dread disease is enormous. What’s more, I don’t want my right to a ventilator to be rationed away to someone younger and healthier, and deemed more deserving.

Yet for many disabled people, a strong, stubborn vein of tenacity and even good humor runs through this wrenching sense of menace.

On social media, a kind of bravura greeted the contagion. To some of us, the initial threat almost felt like nothing new. Many disabled people rarely venture outside anyway, because of access barriers or environmental sensitivities or the cumbersomeness of lugging an oxygen tank or other apparatus. “Wow! Today I learned that the lifestyle I’ve always lived is called shelter-in-place or self-quarantining!” joked one online friend.

“I’m really good at not touching my face,” said another, referring to the fact that he (like me) has never been able to touch his face. We don’t shake hands, either. Plus, those of us in big motorized wheelchairs typically maintain a safe distance from other people — for fear of running over their toes.

Don’t get me wrong. We are scared. We know we can’t entirely self-isolate. Because we rely on outside help, we’re always vulnerable to whatever germs our personal-care aides may, despite their best efforts, inadvertently bring into our homes. It’s a risk we have to take — always. We don’t have a choice.

But we’re accustomed to this contagion-phobic territory. Welcome to the club, nondisabled people.

The rationing of scarce medical resources — particularly the idea that ventilators could be given to young, otherwise healthy patients instead of people like me — has only mobilized us. Online petitions and even lawsuits have ensued to block such blatant and dangerous health-care discrimination. Tennessee has even singled out those with SMA — like me — for exclusion from critical care in an emergency triage. But I’m proud of my disabled brothers and sisters for being among the first to bring this to public attention and taking action.

Like many people with SMA, I already have a lot of medical equipment at home. I have a BiPAP ventilator, an oxygen concentrator, a nebulizer to dilate my airways and loosen secretions, a cough-assist machine that exercises my lungs and helps to clear them, a tracheostomy and a suction machine to suck gunk out when I can’t cough it up myself. I’m not hoarding this stuff the way some people have stockpiled toilet paper. It’s just my standard survival arsenal. Call it disability privilege.

Yes, it’s pleasant to joke in the face of terror, to laugh at the nightmare that is before us. But if I do get sick, I hope I can stay out of the hospital. That’s vital, because there has been alarming discussion that strained hospitals could end up taking breathing devices away from people who use them regularly so that others can have them. This would be ghastly and unfair. We need and use our devices every day.

So help us not get sick. Keep washing your hands, wearing masks and coughing into your elbows. It’s not fair to make those of us who always have to worry about catching something do all the work.

Indeed, I can’t help hoping this crisis leaves some positive long-term changes. Continued widespread telecommuting, for instance, could help reduce the disability unemployment rate, which is twice the national average in the best of times. Expanding the availability of education and entertainment — having more museums open their exhibits to virtual views, say, and more first-run movies released to pay-per-view and streaming services — is another idea disabled people have been clamoring for for years.

In the meantime, though, please don’t cry for us. We know all about facing risks, taking precautions and going on with our lives. That doesn’t make us less afraid. But it might make us experts.

- Ben Mattlin

Our special contributor Ben Mattlin, was born with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a congenital muscle weakness that causes paralysis and related health issues. A highly regarded writer, Ben’s work has appeared in “The New York Times,” “The Washington Post” and “USA Today.” He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and children.

Reprinted from the “Washington Post”

More articles and info about those of us with SCI who are not in wheelchairs. We receive a special discrimination as people see us as “normal” and we have mind-boggling pain and severe mobility issues. Lost my family to this horrible life dynamic. Bring it out into the open aswe are not regarded because we can walk.