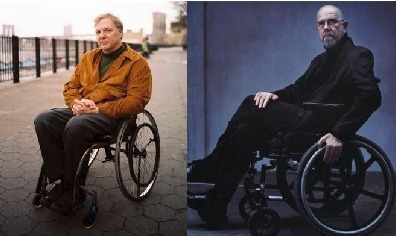

John Hockenberry pictured left, Chuck Close right.

Our talented and fearless blogger, Ben Mattlin, takes on a hot topic— recent sexual harassment admissions by journalist John Hockenberry and famed artist Chuck Close. Both men use wheelchairs. So does Ben.

What’s happening with my people?

In late December, in separate allegations, the esteemed Public Radio host John Hockenberry and world-famous artist Chuck Close were both accused of sexual improprieties. So were many others, of course. But these men both use wheelchairs.

I do, too, but apparently I’m much nicer.

I realize that people with disabilities have been saying for years that they can do anything anybody else can, but this? Do you have to prove it in such a creepy, criminal way? It’s no laughing matter, to be sure. And the accusations against them aren’t entirely identical—Hock reportedly insulted and bullied female coworkers, while Close is accused of making women undress and uttering unwarranted comments about their body parts.

Yet the cases are similar enough that, in the current climate, the public is likely to conflate the two examples.

I don’t know Close, but I’ve met Hock. I interviewed him and his wife, Alison, for an upcoming book about inter-abled romance—that is, unions between people with disabilities and people without them. With their full consent and cooperation, I’d delved into the details of their 20-year marriage. How had I missed the clues that there was trouble in their paradise?

Rolling Role Models Hide Troubling Secrets

Frankly, I’d come to think of Hockenberry as a kind of role model. Yes, a rolling role model. Hadn’t he braved Middle-East war zones as an NPR reporter, wheels and catheters and all? Hadn’t he written a best-selling memoir (its title, Moving Violations, now rings with haunting irony) and performed a well-received one-man show off-Broadway?

Neither Hock nor Close ever made a secret of their disabilities. Without shame or the usual disguises of the paraplegic (framing camera angles for head-and-shoulders-only shots, for instance, or magically appearing behind a desk with no visible means of entrance or exit), Hock had been in front of TV cameras many times, chalking up multiple Emmys. Close was often shown in full-body portraits.

For me, now, these brave images carry the smell of deceit.

Perhaps that’s not entirely fair. Still, how should I square my admiration for these men’s myriad accomplishments with my revulsion at their alleged depredations? Can I still feel proud of, even inspired by, their examples?

Reluctantly, I search through my Hockenberry interview notes. Hock talked about the emotional bubble he put around himself as a defense against feeling overlooked, discounted, or negated. Did that mean something more sinister? Alison told me that his insistence on being strong and independent was a turn-on, initially, though later it became a hindrance. She needed him to learn to be vulnerable, to confide in her, to share his feelings and participate in the give-and-take that’s essential to a good, lasting relationship.

At the time, I took these frank confessions as typical heterosexual relationship chatter. But should I have read between the lines?

No Excuses

What’s most galling to me, though, are the explanations both men have made. “As a quadriplegic, I try to live a complete, full life to the extent possible,” Close reportedly said. “But given my extreme physical limitations, I have found that utter frankness is the only way to have a personal life.”

What on earth does that mean? Does anybody believe it?

Hock’s public apology wasn’t much better. It included this: “Having to deal with my own physical limitations has given me an understanding of powerlessness, and I should have been more aware.”

No, guys, your disabilities aren’t a license to fondle, bully, tease, or otherwise abuse. Your physical limitations are irrelevant—and, please, don’t give the rest of us wheelchair guys a bad rep. It’s your behavior, not your bodies, that are in question. If disability isn’t pertinent to your professional capabilities, then it isn’t to your wrongdoings either. You can’t have it both ways.

I concede that many of us with disabilities may harbor deep-seated feelings of inadequacy. Some disabled people—men and women alike—are sexually insecure, starved for physical affection. The late cartoonist John Callahan, a quadriplegic, used to talk about living at a nipples-eye view of the world, which I took as a comic expression of his horniness.

But such frustrations are no excuse. True, we can and often do get away with stuff. Probably every disabled person has taken advantage of others’ pity at some point. I’ve accepted discount tickets to movies and plays. At Disneyland, I’ve used my wheelchair to cut to the front of the line. Whether or not such perks are justified is debatable. But sexual harassment isn’t among the items signified under the Twitter hashtag #cripswag.

I hope the general public doesn’t come away from these recent news items thinking all crips are creeps. And for those of us with disabilities, the message should be loud and clear: Don’t even think about it. If we don’t want special treatment, then we’re not entitled to special dispensation either.

This is true even if you’re considered a role model.

Ben Mattlin’s new book, In Sickness And In Health: Love, Disability, and a Quest to Understand the Perils and Pleasures of Interabled Romance, will be out later this month.

_________________________________________________________________________

Ben Mattlin is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer. Born in New York City in 1962 with spinal muscular atrophy, a congenital muscle weakness that causes paralysis and related health issues, Mattlin graduated cum laude from Harvard University in 1984. He was one of the first students to do so using a wheelchair. Today, he lives in Los Angeles with his wife, their two daughters, a cat and a turtle.

Ben Mattlin is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer. Born in New York City in 1962 with spinal muscular atrophy, a congenital muscle weakness that causes paralysis and related health issues, Mattlin graduated cum laude from Harvard University in 1984. He was one of the first students to do so using a wheelchair. Today, he lives in Los Angeles with his wife, their two daughters, a cat and a turtle.

“I’m in a wheelchair, he says. “I have a headrest support because I can’t hold my head up. I now drive my chair with a mouth control — a plastic collar around my neck and little itty-bitty joystick I can push with my lips.” And, he adds with a laugh, “I wear glasses.”

Ben is the author of MIRACLE BOY GROWS UP: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity, and the upcoming IN SICKNESS AND HEALTH: Love, Disability, and a Quest to Understand the Perils and Pleasures of Inter-abled Romance (Beacon Press: 2018). He is a frequent contributor to the New York Times and Financial Advisor magazine. His work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and USA Today, and has been broadcast on NPR’s Morning Edition.

Copyright,

Congrats on pursuing the career you dreamed of in those heady L.A. days.