Editor’s Note: In the spirit of the 2022 holiday season, we decided to reprint one of our most popular articles from our frequent blogger, Ben Mattlin. In this story, he uses the familiar fable, A Christmas Carol to make a point about how we must be inclusive to everyone who is in need – not just to those in our immediate circles. Especially during these post-Covid holidays.

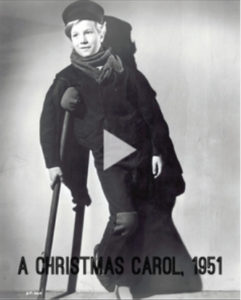

In Charles Dickens’ immortal A Christmas Carol, Tiny Tim—the crutch-using young son of Bob Cratchit—is the epitome of a disability trope: He is inspiring, he is cute, he is doomed.

In Charles Dickens’ immortal A Christmas Carol, Tiny Tim—the crutch-using young son of Bob Cratchit—is the epitome of a disability trope: He is inspiring, he is cute, he is doomed.

Yet sad and pitiful as he may be, Tiny Tim smiles through the pain and famously says, “God bless us, every one.” Every is stressed, because he’s including mean old Mr. Scrooge.

It’s inspiration porn at its worst. And yet…

A Media Staple

Maybe Tim was onto something. What’s wrong with feeling charitable, generous, grateful?

Make no mistake. Inspiration porn IS harmful. It uses images of ordinary disabled people to make nondisabled people feel better about their lives. It objectifies us, separates us from “real” people who live “normal lives.” It seems to say that disabled people’s sole purpose is to brighten other people’s days.

Such throat-grabbing portrayals remain media (and social media) staples, perhaps especially during the holiday season. They are exploited for all kinds of purposes, from garnering sympathy to raising money. But maybe there’s a good side to this phenomenon.

A while back, I published an opinion piece in the Washington Post objecting to the revival of the Muscular Dystrophy Association’s fundraising telethon. I objected to its pity peddling, its cynical use of inspiration porn to extract dollars from viewers’ pockets. I’d written about this charity’s mawkish telethons before and, when the telethons ceased a decade ago, I thought I and other protesters had won. The telethon was dead! But apparently, I was wrong.

The arguments I made are old ones: Disabled people don’t need or want pity. Using pity to raise money doesn’t really help us. In fact, it’s the opposite; it does us a grave disservice.

Holiday Charities

But there is another, more nuanced problem with treacly fundraising appeals—the sort that inundates us around the holidays. Participating in charity events enable people to think—wrongly—that they’ve achieved something. But the fact is, nothing’s really changed at all. And without that comforting illusion, they might be more willing to agitate for genuine political change, which could make an actual difference.”

A Pretense of Conscience

In a nutshell, charity fundraisers like the MDA Telethon create an excuse for inaction and exploit the “pretense of a conscience.”

If a health-care charity provides medical exams and equipment, for example, doesn’t it in effect relieve the general public—or the government—of the obligation to provide care for some of those who need it? Don’t these individual efforts, however well intended, lull people into a false sense of accomplishment? Don’t they thereby detract from the greater good?

I know, this sounds gloomy. It’s good for people to give to charity, right? A little charity is better than none. And for many of us, it’s easier to donate money than time or effort. We’d rather voluntarily give a few bucks to a private organization than take up broad-based political causes.

But why stop there?

“I gave at the office”

When people respond to a charitable appeal, they feel good, they pat themselves on the back. They may think they’re done. They’ve done their part. But giving shouldn’t absolve you of being kind and fair and generous in general. It shouldn’t become an excuse for inaction. You can’t say, “I gave at the office,” and then go out and be a jerk. You ought to continue caring about and doing good deeds for other people. You still have to help those who need help.

In the Dickens story, Scrooge feels sorry for Tiny Tim and is ultimately moved to give the family extra money so Tim can get better and live longer. That’s great, but he’s not moved to agitate for better social services on a wider scale. He may help one kid, one family, but Tiny Tim isn’t the only one who needs help. Scrooge’s donation to the Cratchit family doesn’t do anyone else any good.

The narrator seems to recognize this flaw. By the end, we’re told that Scrooge changes his ways and starts giving more to all who need it. Not just at Christmas, but all year long.

That, I think, is the idea. That’s a worthy message and goal. Even if it sounds corny, trying to act kindly toward everyone, all the time—to bless everyone, as Tiny Tim says—is the best policy.

Ben Mattlin

Ben Mattlin is a frequent contributor to the Washington Post, New York Times and Financial Advisor magazine. His work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and USA Today, and has been broadcast on NPR’s Morning Edition. Ben is the author of Disability Pride: Dispatches from a Past ADA World, MIRACLE BOY GROWS UP: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity, and IN SICKNESS AND IN HEALTH: Love, Disability, and a Quest to Understand the Perils and Pleasures of Inter-abled Romance

Mattlin is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer, author and frequent blogger for FacingDisability.com. He was born with spinal muscular atrophy, a congenital muscle weakness that causes paralysis and related health issues.

Leave a Reply