Editor’s note:

We asked our favorite guest blogger, Ben Mattlin, to tell us a story for Valentine’s Day. He selected a piece from his book, In Sickness and In Health Love, Disability, and a Quest to Understand the Perils and Pleasures of Interabled Romance. It’s a lively and heartwarming love story of a man with a disability who meets and falls in love with an able-bodied woman – they are one of the most memorable of the interabled couples Ben highlights in his book.

Ben’s introduction:

For Valentine’s Day, here’s an edited excerpt from my book about interabled relationships. I’m revisiting this with some sadness, though, as one of the people interviewed here died recently (I’m not saying which, to preserve their anonymity):

Felicia and Juan (not their real names) live in Arizona. Juan was born with osteogenesis imperfecta (O.I.), a congenital condition that gives him extremely brittle bones and makes him barely three feet tall. Yet his muscular arms propel him in a small wheelchair with riveting power and grace. I soon learn he’s also, as my aged father might say, a character.

From the book:

From the book:

Felicia, his wife of four years, is fit and healthy-looking and outdoorsy—a passionate speaker with long, flowing auburn hair and a smooth, youthful complexion.

They are both motivational speakers and life coaches, though those aren’t the terms they prefer. Rather, this dynamic, engaging couple like to be called “entrepreneurs.”

Juan raises and lowers his thick eyebrows with comedic precision, and his tongue constantly flicks across his smiling lips. At thirty-six, he shaves his head bald and sports a scruffy soul patch. What’s most noticeable is his perpetual devilish grin, punctuated by eyes as bright and twinkly as halogen bulbs.

Felicia speaks first. “It’s actually very complimentary, what we do,” she says. “Juan does keynote speeches all and runs his own events, but he also does some one-on-one coaching and therapy. I’m more involved in the coaching side, but I’ve also spoken on stages.” Some of their clients cross back-and-forth between them.

Juan stays quiet for the moment. He’s a natural-born entertainer. With the self-assured voice of an experienced actor, he explains that he decided at an early age to treat his disability as a gift rather than a burden. He set on a mission to tell the world that life is what you make of it, your destiny is in your hands. It’s a spiel he’s delivered to crowds around the world.

Felicia is more of a one-on-one life coach, but she too is all about self-motivation.

In 2008, a mutual friend suggested they connect on Facebook because they were in such similar industries. More than a year passed before they met in person, at a conference. After, they kept in touch. “We were friends. But he definitely did not want to be in the friend zone,” she recalls.

“I wasn’t really interested in having more friends,” Juan says. “I already had enough women friends.” He makes it sound like innuendo. Felicia chuckles.

In time, he talked her into visiting him, and she admits there were “great sparks.”

“We had immediate chemistry,” Juan insists. “We had so much in common, and I had complete confidence we weren’t going to stay just friends.”

Back then, he was still living with his parents in an inaccessible home where he had little independence. His father would carry him in from the car to a wheelchair on the first floor. But his bedroom was on the second floor, so he had to be carried upstairs every night. He moved about his bedroom by scooting around the floor with his hands. The bed was on the floor, so he could move in and out of bed but couldn’t shower or get food on his own. Felicia was surprised by the arrangement. His parents loved him, but they had no clue. So together they devised ways to empower him to greater independence.

The house they now share is on one level. The accessible bathroom has a roll-in shower and a toilet onto which he can transfer himself. The house also has two kitchens—a “regular” one for Felicia and a separate shorter one in which he can reach the refrigerator, the grill, the toaster oven, the faucet, and all the cooking utensils. “None of that stuff he had in the past,” she says.

Juan makes one of his funny raised-eyebrow faces and says, “Felicia was the coolest woman I’d ever met, so I knew I had to mature quickly to keep a woman like her.”

Juan is a performer. He soaks up adulation by conveying indomitability, by telling jokes and engaging—not challenging—his audiences. Why shouldn’t he use the assets he was born with? To put it another way, if people are going to be inspired anyway, just seeing him out and about even though he looks like you could fold him into a backpack, why shouldn’t he take control of the message and charge people for it?

He concedes he was reluctant about these lifestyle changes at first. “I didn’t believe it was possible, and I didn’t know I’d like it so much, this independence,” he says. His biggest fear was that he was too fragile to be autonomous. “I knew a bunch of people at the O.I. Foundation,” he explains, “and most of the ones who had more independence didn’t fracture as often as I do.” He admits he’s still learning as he goes. “But I’m in better shape now physically as well as emotionally,” he says.

Before closing our conversation, I ask about the give-and-take between them. It’s obvious what Felicia has done for Juan—helping him move out of his parents’ house, enabling him to find his independence—but what does he give her?

Juan moves forward in his wheelchair. “Sex!” he says.

This time, we all three chuckle.

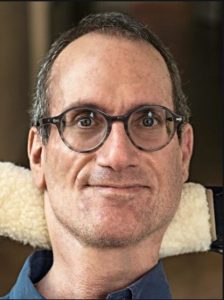

Ben Mattlin

Ben Mattlin is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer, author and frequent blogger for FacingDisability.com. He was born with spinal muscular atrophy, a congenital muscle weakness that causes paralysis and related health issues.

Ben is the author of MIRACLE BOY GROWS UP: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity, and IN SICKNESS AND IN HEALTH: Love, Disability, and a Quest to Understand the Perils and Pleasures of Interabled Romance . He is a frequent contributor to the Washington Post, New York Times and Financial Advisor magazine. His work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and USA Today, and has been broadcast on NPR’s Morning Edition.

Leave a Reply